By Celie Dailey & Orrin H. Pilkey

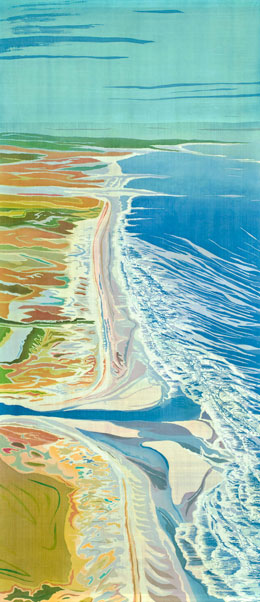

Edingsville Beach (SC), Batik on silk by Mary Edna Fraser

2009, 79” x 35”

One important societal need, in the face of climate change, is to stop hardened structures from being placed along our sandy barrier island shorelines.

Unlike buildings, which the hard structures are supposed to protect, barrier islands are flexible, dynamic, and are even capable of landward migration in response to sea level rise.

Two of the problems with hard structures are that they cause the eventual loss of the beach and rarely protect the buildings from the really big storm. A beachside lot on a barrier island loses its mystique when there is no beach. The desire for a beach house or hotel view of the ocean overrides the obvious hazards of beachfront living and the eventual need for hard structures contributing to the loss of beaches.

In a time of rising seas, it is senseless and dangerous to build on barrier islands. With sea level rise expected to reach 3 feet above the present level by 2100, barrier island development will become impossible unless protected by massive seawalls around entire islands.

An entire Atlantic Coast barrier island community getting wiped out is not new news. Over the years a number of small communities have disappeared. Some have been lost to the waves of big storms, such as Edingsville, South Carolina, in 1893. Others have fallen into the sea more gradually because of a combination of storms and shoreline erosion, such as Broadwater, Virginia, in 1941. Still others were abandoned in the face of perceived future storm hazards, a wise move. Diamond City, North Carolina, for examples, was abandoned and its buildings moved to safer sites on the mainland after three close calls with closely spaced hurricanes in the late 1890s but before significant damage to buildings had occurred.

In pre-Civil War South Carolina, Edingsville was a high-end resort community with sixty houses, two churches, and a tavern. Wealthy people from Charleston and nearby Edisto Island escaped to the resort to enjoy the seabreeze and avoid the summer malarial mosquitoes on the nearby coastal plain interior. A drawing of the community shows people promenading on the beach, fully attired in formal clothing, following the customs of the day. An 1851 Geodetic Survey chart shows the houses neatly spaced across the entire island. After the Civil War, the wealth that supported the island community diminished and the town fell into disrepair. The end came when the great Sea Island Hurricane of 1893 struck and destroyed all the houses.

Subsequent erosion and island migration reduced the island to a narrow strip of sand less than a hundred feet wide. The old village, perhaps a harbinger, is now four hundred meters (one-quarter mile) offshore. Still, bits of brick, pottery and nails from the village often wash ashore in storms.

Mary Edna Fraser caught the image that inspired her batik in 1983 with her Nikon 35mm film camera. Orrin Pilkey recognized the beach as the former Edingsville location. The art was created in 2009 at Orrin’s request. Mary Edna considers this scene her “aerial backyard,” south of Charleston, South Carolina. Mary Edna often depicts regions that are free of the marks of man across the landscape, inspiring reverence for the dynamic power of the Earth.

The batik on silk of Edingsville Beach is featured in Our Expanding Oceans, a comprehensive art and science exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh which features the collaboration of Mary Edna Fraser and Orrin H. Pilkey and supports the newly published text by Duke University Press, Global Climate Change: A Primer.

The book is co-authored by geoscientist Orrin H. Pilkey and his son, Keith C. Pilkey, with art by Mary Edna Fraser. The exhibit, Our Expanding Oceans, is on view until November 6, 2011 and is scheduled to travel in 2012.

Our Expanding oceans, And Global Climate Change: A Primer, Article And Video, Coastal Care

Artist And Scientist Make A Natural Pair: United They Are An Educational Force, Coastal Care

Nil Delta Desert Islands: An Artist And A Scientist Symbiotic Point Of View, Coastal Care