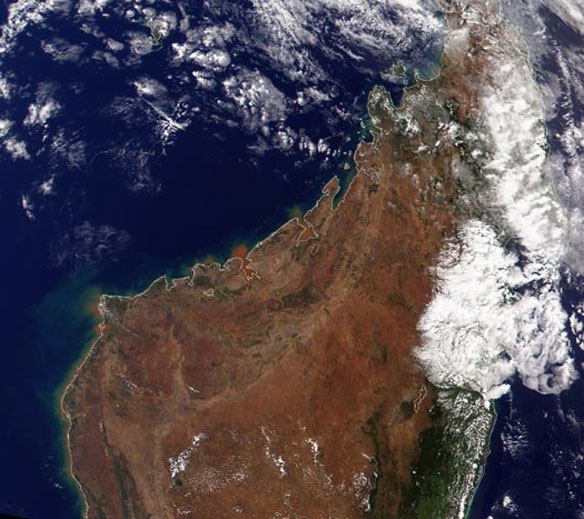

Betsiboka Estuary, Bombetoka Bay and Mahajamba Bay, Northwest Coast, Madagascar. Estuaries are regions where fresh water from rivers and salt water from the ocean mix, and they are among the most biologically productive ecosystems on Earth. This astronaut photograph, taken from the International Space Station, highlights two estuaries along the northwestern coastline of Madagascar.

Excerpts; by William L. Stefanov, Jacobs/ESCG at NASA-JSC / NASA Earth Observatory

The Betsiboka Estuary on the northwest coast of Madagascar is the mouth of Madagascar’s largest river and one of the world’s fast-changing coastlines.

Nearly a century of extensive logging of Madagascar’s rainforests and coastal mangroves has resulted in nearly complete clearing of the land and fantastic rates of erosion.

After every heavy rain, the bright red soils are washed from the hillsides into the streams and rivers to the coast. Astronauts describe their view of Madagascar as “bleeding into the ocean.”

The Mozambique Channel separates the island from the southeastern coast of Africa. Bombetoka Bay (image upper left) is fed by the Betsiboka River, and is a frequent subject of astronaut photography due to its striking red floodplain sediments. Mahajamba Bay (image right) is fed by several rivers, including the Mahajamba and Sofia. Like the Betsiboka, the floodplains of these rivers contain reddish sediments eroded from their basins upstream.

The brackish conditions (a mix of fresh and salt water) in most estuaries invite unique plant and animal species that are adapted to live in such environments.

The salty waters of the Mozambique Channel penetrate inland to join with the freshwater outflow of the Betsiboka River, forming Bombetoka Bay. Numerous islands and sandbars have formed in the estuary from the large amount of sediment carried in by the Betsiboka River and have been shaped by the flow of the river and the push and pull of tides.

This image from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA’s Terra satellite shows Bombetoka Bay just upstream of where it opens up into the Mozambique Channel. In the image, water is sapphire and tinged with pink where sediment is particularly thick. Dense vegetation is deep green. Along coastlines and on the islands, the vegetation is predominantly mangrove forests. Acquired on August 23, 2000.

The mangroves of Madagascar are very similar to those of the African mainland. Nearly all of hardy shrubs and trees of mangroves in Madagascar occur along the low-lying western coast. They are common in and around Madagascar’s estuaries, and the largest mangrove stands are found at Mahajamba Bay, Bombetoka Bay, south Mahavavy and Salala, and Maintirano.

Mangroves occupy a stretch of coastline of approximately 1000 kilometers in length. Along the northwest coast of Madagascar, mangroves and coral reefs partner up to create dynamic, diverse coastal ecosystems.The mangrove forests capture river-borne sediment from the interior lands that threatens both reefs and seagrass beds, and that would smother coastal reefs, while reefs buffer the mangroves from pounding surf.

Mangroves also provide shelter for diverse mollusk and crustacean communities, as well as habitat for sea turtles, birds, and dugongs.

Estuaries also host abundant fish and shellfish species, many of which need access to fresh water for a portion of their life cycles. In turn, these species support local and migratory bird species that prey on them.

But, a century of extensive logging of Madagascar’s rainforests and coastal mangroves has resulted in nearly complete clearing of the land and fantastic rates of erosion, threatening the health of the estuaries and their entire ecosystems.

Once almost entirely covered in green, lush vegetation, Madagascar has witnessed the destruction of an estimated 80 percent of its indigenous forests. The now reddish-brown terrain can be seen in this true-color image of northern Madagascar. Image by Brian Montgomery, Robert Simmon, and Reto Stöckli / NASA

Driven by a need to feed an ever increasing population, an estimated 18-20 millions residents in 2011, the people of Madagascar continue to encroach on the forests that lie along the coasts. Most of what is left of Madagascar’s native vegetation can be seen on the right side of the island in dark green on the image above.

Mangroves are threatened by human activities such as urban development, overfishing, and erosion caused by tree-cutting in the highlands. Some mangrove areas have been converted to rice farming and salt production.

The Malagasy Government encourages development of shrimp aquaculture and this habitat type is being increasingly used by the private business sector.The Mahajanga Aquaculture Development Project, a joint venture between Madagascar and the Japan International Cooperative Agency, strings along the coastal region at the mouth of the estuary (inset images). This project is a shrimp farm and has been developed since 1999.

Near water, shrimp and rice farming are then common, the rectangular blue areas near the top center edge may be shrimp pens while coffee plantations abound in the surrounding terrain. (see photo inset below).

Successive images taken by astronauts show increasing numbers of ponds constructed between 2000 and the present.

Coastal aquaculture projects are frequently controversial, pitting the protection and viability of coastal ecosystems (especially rapidly disappearing mangrove environments), against badly needed industry in developing countries.

Additionally, one impact of the extensive 20th century erosion is the filling and clogging of coastal waterways with sediment, a process that is well illustrated in the Betsiboka estuary. Increased sediment loading from erosion of upriver highlands threaten the health of the estuaries. In particular, the silt deposits in Bombetoka Bay at the mouth of the Betsiboka River have been filling in the bay. In fact, ocean-going ships were once able to travel up the Betsiboka estuary, but must now berth at the coast.

A bad situation is made worse when tropical storms bring severe rainfall, greatly accelerating the rates of erosion.

As an illustration, astronauts aboard the International Space Station documented widespread flooding and a massive red sediment plume flowing into the Bestiboka estuary and the ocean in the wake of Tropical Cyclone Gafilo, which hit northern Madagascar on March 7th and 8th, 2004 (top image).

Widespread flooding and a massive red sediment plume flowing into the Bestiboka estuary and the ocean.

A comparative image here, taken in September 2003 shows normal water levels in the estuary.

Bombetoka Bay, Madagascar, NASA