By Harold R. Wanless, Professor and Chair, Department of Geological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Miami and by John C. Van Leer, Associate Professor, Division of Meteorology and Physical, Oceanography, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami;

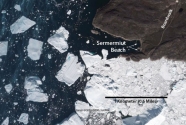

A most remarkable pair of small pocket beaches are nestled among the granitic cliffs at the mouth of Jacobshaven Icefjord. This Icefjord is about a third of the way up the western coast of Greenland, 250 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle. Sermermiut Beach is near the end of the – km board walk south of the fabulous, growing tourism town of Ilulissat. This boardwalk takes you out to overlook the mouth of a major Icefjord that drains ice from 1/7 of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

“Sermermiut, in Greenlandic “the place of the glacier people,” includes evidence of all three major Inuit periods of migration and settlement.”

— Harold R. Wanless & John C. Van Leer

The Icefjord is over 1000 meters in depth, about 5-7 kilometers in width, extends about 60 kilometers inland to the edge of the Ice Sheet, and then continues in deep channels far inwards under the Ice Sheet.

Eight thousand years ago a glacial tongue of the Ice Sheet extended all the way out of this Icefjord and deposited a terminal moraine of gravel at the mouth of the fjord. This gravel ridge is now about a marine sill 200-250 meters deep and arcs across the mouth of the Icefjord just off of Sermermiut Beach. Further into the Icefjord, fjord water depths increase from 1,000 to 1,500 meters in depth. The calving front of the ice has now retreated some 65 kilometers inward beyond the Ice fjord, into and under the Ice Sheet.

The forward speed of the Ice Sheet ice moving to the calving front has accelerated 6 fold (to some 30 km/year) in the past decade and the frequency of calving at the front has increased from a few times a week to several times a day. Locals say that the number of huge icebergs has diminished because of more intense fracturing associated with this acceleration, but the number of 100-150 meter high icebergs temporarily stranded on the gravel moraine adjacent to Sermermiut Beach is still very impressive and their splitting, rolling and collapsing is a frequent source of tsunami energy to the beach.

The beach is called Sermermiut. It is the prehistoric habitation site there (studied but invisible). It is a spectacular beach of gravel and sand studded with small to large chunks of ice (bergy bits) stranded there by tsunamis created by the frequent breaking and rolling of nearby giant icebergs temporarily stranded on the 250 meter deep moraine at the mouth of the Icefjord.

The Ancient Inuit settlement of Sermermiut dates from about 2,500 BC and is a major element of this diverse World Heritage site, the adjacent Jacobshaven Icefjord is the most productive in Greenland. Sermermiut in Greenlandic means “the place of the glacier people.” It includes evidence of all three major Inuit periods of migration and settlement. Archeological evidence of the following cultures were found: 1) Saqqaq culture 2500-100 B.C.; 2) Dorset culture 500B.C. – 200 A.C.; and 3) Thule culture 1000 – 1850 A.C.

“ … people are warned against venturing down onto the beach because of these frequent and rapidly arriving tsunami surges which range up to about 10 meters.”

— Harold R. Wanless & John C. Van Leer

This “beach of the month” has open water offshore in summer, maintained by fjord’s circulation with outward flowing (about 1.5 kilometer / per hour velocity) melt water at the surface. Winter pack ice formed a convenient base for seal hunting and ice fishing for Greenlandic Halibut. So, this protected area along the northwest edge of an exceptional biologically productive fjord has been prime real estate throughout the millennia and supported the largest town in Greenland of about 20 dwellings in 1737, according to the first Danish missionary Poul Egede.

A number of rectangular depressions mark sod dwelling sites which were used as winter quarters as recently as the early Danish colonial period according to Egede. The walls of these homes were similar to Norse construction, except there were alternate courses of sod and flat stone for added structural stability. During the summers, when the Inuit were exploiting remote food sources, the roof skins and poles were removed and used as portable tents, so the inside of the sod homes could air out.

Importantly, today people are warned against venturing down onto the beach because of these frequent and rapidly arriving tsunami surges which range up to about 10 meters. The close source of tsunamis would give very little warning time. While large calving bergs sometimes sound like very large artillery, rolling bergs make little or no sound. We watched a small tsunami from the breakup of a large iceberg far out in the Icefjord.

Some beaches are amazing just to appreciate from a distance.