By Gary Griggs, Distinguished Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Director Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, California

Every year the dredge at the Santa Cruz Small Craft Harbor along central California’s northern Monterey Bay sucks up about 250,000 cubic yards of sand, on average, from the entrance channel and pumps it out onto Twin Lakes Beach where it continues its journey down coast (Figure 1). If it were put in dump trucks, it would fill about 25,000 of them, but the waves can move all that sand without any human labor, and without any noise or carbon emissions. The waves, however, can’t easily move it across the harbor entrance without the channel plugging it up.

The sand moving along the Santa Cruz coastline starts its shoreline journey about 75 miles upcoast, 15 miles south of San Francisco’s Golden Gate. Sand reaches the beaches of this section of coastline from small creeks and rivers and from the erosion of the sandy bluffs. After being carried southward by breaking waves from the northwest, down the San Mateo and Santa Cruz County coasts, it enters Monterey Bay (Figure 2).

The beach immediately upcoast of the harbor was much narrower under natural conditions (Figure 3), but with the completion of the Santa Cruz harbor in 1965, the new jetties became a dam for littoral drift. The beach immediately upcoast of the harbor (known historically as Castle Beach because of an old castle built on a low bluff (Figure 4), but today more often known as Seabright Beach), widened by as much as 500 feet as millions of cubic yards of sand were trapped behind the jetty over the next several decades (Figure 5).

“The dredging is an endless and thankless task, but we really don’t have much choice if we want to maintain the harbor… ”

— Gary Griggs

Within a few years, however, some of that littoral sand was carried by the northwesterly waves around the end of the west jetty into the entrance of the new harbor. Deposition of the sand soon led to shoaling of the boat channel and threatened to close the harbor. Dredging was needed and has been needed ever since (Figure 6). Nine and a half million cubic yards of sand were dredged out between 1964 and 2014, enough to fill the entire Superdome in New Orleans twice.

The dredging is an endless and thankless task, but we really don’t have much choice if we want to maintain the harbor. If its any consolation, many other California coastal harbors share the same problem – how to deal with all the littoral sand that continues to move into their entrance channels on its path down along the shoreline.

Santa Barbara harbor dredges a bit more than Santa Cruz, about 310,000 cubic yards every year on average (Figure 7). A short distance down coast, Ventura harbor must move about 600,000 cubic yards a year (Figure 8). A few miles farther east, Channel Islands Harbor dredges close to a million cubic yards, every year (Figure 9). The sand removed from Channel Islands Harbor has already been

pumped out of the Santa Barbara and Ventura harbors, so is eventually dredged out of three different harbors. At $5 a cubic yard or more, these are high annual maintenance costs. And the problem will never go away and will gradually get more expensive as fuel and labor costs increase over time.

Not all of California’s harbors have sand and dredging problems. Neither Moss Landing (Figure 10) nor Monterey harbors (Figure 11) do any significant dredging. King Harbor in Redondo Beach doesn’t need to move sand (Figure 12), and Dana Point Harbor has never been dredged (Figure 13). Why is that? Why do we have to move 250,000 cubic yards of sand every year out of the Santa Cruz Harbor, and 20 miles away, Moss Landing has an entrance channel that doesn’t need to be dredged? Just like real estate, it’s all about location, location, location.

Sand moves along the shoreline of California and along many coastlines around the world within essentially self – contained beach compartments or littoral cells. The sand that moves along the shoreline of northern Monterey Bay is in a completely different compartment than the sand coming out of the Golden Gate or found along the beaches of Santa Barbara or Santa Monica.

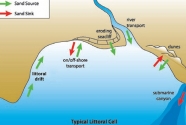

Each cell or compartment consists of 1) sources of beach sand (rivers, streams and some bluff erosion along California’s coast); 2) littoral drift or longshore transport, driven by waves typically coming from the northwest, which move sand southward along most of the California coastline; and 3) sinks, or places where sand leaves the shoreline (Figure 14). In California the major sinks are either sand dunes, such as those along the shoreline of southern Monterey Bay or Pismo Beach, where wind transports the sand inland off the beach; or deep submarine canyons, where sand flows offshore and down slope to the deep – sea floor 10,000 to 12,000 feet below.

“Moss Landing, Monterey, King, and Dana Point harbors are all good examples of low or no maintenance harbors because of their locations… ”

— Gary Griggs

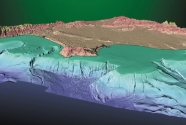

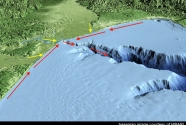

Monterey Submarine Canyon, which bisects Monterey Bay (Figure 15), is one of the largest in the world, but there are many others along the California coast that also serve as sinks for beach sand: Carmel Canyon, Hueneme Canyon, Mugu Canyon, Redondo Canyon and Newport Canyon to name a few (Figure 16). The Santa Cruz beach compartment begins north of Half Moon Bay and terminates at Moss Landing where the head of Monterey Canyon extends almost to the beach. After being transported for 90 miles along the shoreline, the sand that began its journey near San Pedro Point, about 15 miles south of the Golden Gate, disappears offshore right at the entrance to Moss Landing harbor (Figure 17). As a result, very little sand enters the harbor so there is almost no dredging needed.

The beach sand in the Santa Barbara littoral cell is carried by longshore transport about 145 miles from north of Pt. Conception to the Mugu Submarine Canyon near Pt. Mugu. Along this route the sand is trapped in three different harbors, where it must be dredged our regularly, and is augmented by sand from two large rivers, the Ventura and Santa Clara. The littoral drift rate is about a million cubic yards a year near the downcoast end of the cell at the Channel Islands Harbor. This translates to huge annual dredging costs.

Wherever harbors have been constructed in the middle or downcoast ends of beach compartments with high littoral drift rates, annual and costly dredging of large volumes of sediment is inevitable if the harbor entrances are to be kept open for boats year round.

Where harbors have been built either between beach compartments, however, or at the upcoast ends of cells where littoral transport rates are still low, maintenance dredging is minimal or not required at all. Moss Landing, Monterey, King, and Dana Point harbors are all good examples of low or no maintenance harbors because of their locations. Moss Landing and King harbors were located adjacent to submarine canyons, Monterey Submarine Canyon and Redondo Submarine Canyon respectively. Almost no sand enters either harbor from the beach. Monterey and Dana Point were placed at the beginning of littoral cells and have virtually no dredging costs.

We can think of these beach compartments like bank accounts. Sand or money go in or are deposited, and sand or money go out, whether as cash, checks, or credit cards. As long as the amount of sand or money leaving the cell or being taken out of the account isn’t greater than what is being deposited or coming in, the account is in balance and the beaches remain stable. However, wherever the flow of sand into the compartment is trapped, whether by dams, debris basins, or sediment removal on rivers or streams, or interrupted or removed as it moves through the compartment, by the construction of long jetties or breakwaters along the coastline, or sand mining from the beach, the bank account is overdrawn and beach erosion and shoreline retreat will result.