By Nelson Rangel-Buitrago, Grupo de Geología, Geofísica y Procesos Marino-Costeros, Universidad del Atlántico Barranquilla, Atlántico, Colombia and William J. Neal, Department of Geology Grand Valley State University Allendale, Michigan.

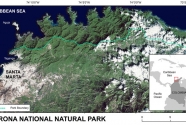

Colombia’s Caribbean coast has a rich geological, biological and cultural diversity that is reflected in the complex coastal zone extending from the border of Panama to that of Venezuela. One of the most spectacular regions in both this diversity and scenery is the Tayrona National Natural Park (TNNP), a coastal reach of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the highest coastal mountain range in the world, with peaks topping out at 5,700m (18,700 ft). This mountain complex stands separate from the related Andes, and forms the seashore along its northern border. The rugged, remote area was a barrier to settlement, and has remained a natural Eden in terms of ecozones and the rich diversity of its flora and fauna. Fortunately, the Colombian government recognized that the 20th century’s rapid increase in expanding settlements and urbanization were threatening the country’s natural areas, and established a system that now comprises 59 National Natural Parks, protecting 126.023 km2 equivalent to 11% of the country’s total surface area. Tayrona National Park is perhaps the most famous of these parks, and is the gem of the Caribbean coast in terms of its scenery and diversity of both terrigenous and marine life. Created in 1964, TNNP stretches along the coast from the western Bahía de Taganga near Santa Marta city to the mouth of the Río Piedras, 35 km to the east, and covers some 120 km2 of land and 30 km2 of the sea (Figure1).

TNNP is the northwest coast of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and the area of the park corresponds to a complex geologic zone underlain by Cretaceous metamorphic rocks and Tertiary igneous intrusives. Valleys formed from streams eroding weaker rocks, or by erosion along faults, and were flooded to produce the long embayments and coves, particularly in the western part of the park, between the resistant headlands. These ridges terminate at the coast, often in seacliffs 100 to 150 m (330 to 490 ft) high (e.g. Arrrecifes, Cañaveral, Chengue, Gayraca, Cinto, Neguanje, Concha, Guachaquita). These rocky coasts have a variety of other erosional features such as sea stacks, scarps, shore-platforms and large granite boulders strewn along the shore (Figure 2).

“The wide variety Fauna in the two ecosystems, from mountains into the sea, includes fascinating wildlife such as the black howler and titi monkeys, red woodpeckers, iguanas, jaguars…”

— N. Rangel-Buitrago & W. J. Neal

The combination of geology and the varied climatic zones due to the ranges of coastal orientations, topographic elevations, and rainfall (0 to 975 mm/yr (38 inches), creates the scenery, and varied ecozones. The extreme western part of the park is arid, with light-brown hills and xerophytic plant species such as cacti. The central and eastern parts of the park are wetter and more verdant, widely covered by rainforest. May, June, and September to November are the wettest periods. The Flora is characterized by this environmental influence of rainfall depending on the sector, from tropical dry forest to rain forest and mangroves.

The wide variety Fauna in the two ecosystems, from mountains into the sea, includes fascinating wildlife such as the black howler and titi monkeys, red woodpeckers, iguanas, jaguars (which are rarely seen as they hunt at night), a variety of lizards, tropical marine life including reefs, and more than 400 species of birds, such as eagles, condors and the odd pet parrots kept at the restaurant at Arrecifes. Below the clear waters is an array of marine life, popular with snorkelers. All of these features provide an ideal place to commune with Nature, and activities include beach combing, snorkeling, boating, fishing, and diving. Hiking trails provide access for birding, exploring nature, and visiting archeological ruins of an ancient city of the Tayrona people. This palate of beauty, both landward and seaward of the shore, makes the Tayrona beaches an experience unique (Figure 3).

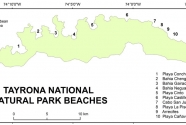

And the more than 20 beaches are the park’s biggest attraction, linking the stunning scenery of mountains, clear blue to azure water conditions, white to golden sands (derived mainly from weathered granite cliffs), creek mouths, and back-beach vegetation (Figure 3). The beaches range from linear, to large pocket beaches at the ends of the longer bays and smaller pocket beaches in coves (Figure 4).

Western Beaches

The great elongate bahias (bays) characterize the western shore of the park (Figure 4). Typically large pocket beaches have formed on the most inner-shores of these bays, but smaller coves on their margins sometimes have pocket beaches. Access is by car from the city of Santa Marta and by boat from Taganga.

Playa Concha, a long pocket beach, is the most popular western beach because there is easy access and facilities (Balneario de Villa Concha). The area is popular for swimming and boating (Figure 5).

Bahia Chengue has a couple of smaller pocket beaches. Its only entry point is by using maritime transportation, but the access to this beach is prohibited because it is the biggest Coral Reef reserve in Tayrona park.

Bahia Gairaca also has two pocket beaches, Playa Hermosa and la Playa del Amor (Figure 6).

Bahia Neguanje looks like a double-wide embayment compared to adjacent Bays, and has three well-developed pocket beaches. Seven Waves Bay owes its name to the strong waves and rip currents there that severely limit maritime activities (Figure 7). In addition, on its eastern flank are Playa Cristal and Playa del Muerto, small white pocket beaches fronted by clear water of blue and green hues, and popular with snorkelers and boaters.

Playa Cinto is the pocket beach at the terminus of the last long embayment to the east. The blue water contrasts with the dark creek, and the area is a good example of the dry-climate vegetation (Figure 8). Cinto and Neguanje are distant by road access. A few additional pocket beaches are located farther east, but lack of access deters beach users.

Eastern Beaches

Road access to the park is limited, and the main eastern entrance provides parking, and then access to the beaches and associated campgrounds is by foot or horseback. Several linear beaches, often with associated creek mouths, occur in this area including Playa Tayrona and the following:

Playa Castilletes, located nearer to the east entrance road, is usually used as a small camping area, convenient to Playa Canaveral.

Cabo San Juan de Guia is a tombolo and the most famous beach of the park; here many visitors spend most of the time because of the scenery and an ideal swimming beach (Figure 9). The beach is on the west side of the cape, as well as a couple of small half-moon coves with pocket beaches.

Playa La Piscina, a small beach located between Arrecifes and Cabo San Juan, is a busy and popular beach because the calm water conditions favor safe swimming (Figure 10). Also, the location is convenient to most all of the eastern park’s campsites.

Arrecifes beach is one of longest stretches of beach in the eastern part of the park (Figure 11), and one of the most popular. Great rounded granite boulders add to the scenic beauty (Figure 12), and during the rainy season there is a freshwater lagoon behind the beach, where alligators can occasionally be glimpsed.

“The more than 20 beaches are the park’s biggest attraction, they range from linear, to large pocket beaches at the ends of the longer bays and smaller pocket beaches in coves…”

— N. Rangel-Buitrago & W. J. Neal

Playa Cañaveral is another beach offering accommodations, but generally has fewer visitors than most of the other beaches in the park. This long beach is much narrower than other beaches in the area, but is a tranquil setting with palm trees, a thin strip of white sand and the turquoise ocean. Here beachcombers will find patches of dark heavy-mineral sands and interesting wrack lines (Figure 13).

Safety

As with all beaches, approach with caution. Take into account the possibility of rip currents (Figure 14). Some of the Tayrona beaches are not suitable for swimming, though you can take a dip and snorkel (with great care) at selected sites. Refer to the Park rules and warnings before your visit (Tayrona National Natural Park web site).

Tourism: what are the limits?

Due to better security conditions, recent peace agreements, and global promotion via the internet, Tayrona Park has become a popular destination for both national and international tourists. Although the inland area of the park has much to offer, the beaches, with Eden as a backdrop, are the areas where visitors congregate. At present, tourism represents one of the most important economic activities, and development capacity appears to be almost limitless. But is it? Park tourism increased from 228,941 visitors in 2009 to 391,442 in 2016, and growth is expected to continue at this pace (Rangel et al., 2013). Such increases in tourism numbers will become unsustainable in the immediate coming years if left unregulated. Uncontrolled tourism into the surrounding areas also will intrude upon both the biota as well as the daily lives of indigenous inhabitants. Already the large numbers of visitors during the high season detract from the world-class charms of the park (Figure 15).

The park attempts to manage human impacts by limiting vehicle access, but heavy use by boaters can offset this in terms of noise, congestion, pollution, and the conflicting use of boats vs. swimmers (Figure 16). Park rules also are aimed at controlling pollution and congestion (e.g., restricting entry of plastic bags, pets, alcoholic beverages, surf boards; requesting visitors to take their garbage and refuse with them when they leave the park), but the numbers of people in camp grounds for example create septic wastes that find their way into surface runoff, groundwater, and into the beach.

Flotsam as seen in wrack lines and in along-shore current deposits show both natural materials, typically brought down by rivers and creeks (e.g., logs, tree limbs, vegetation) as well as waste generated by beach users, boaters, and hikers (Williams et al., 2016). At Seven Waves Bay one can usually find a beach cover of 1000s of items of general litter (Figure 17). This beach is a sink for plastic bottles, shoes, food packaging, ropes, tires, plates, and other plastic and polystyrene materials. In such a case, the adverse effects produced by the litter overcome the aesthetics of the coastal scenery. Stronger actions are necessary to upgrade scenic beach quality (Williams et al., 2016).

In 2015 and again in 2017 the park was closed for short periods to all except for indigenous groups who live within the park area “for ecological, environmental and spiritual healing” (Colombia Travel Blog, 2017), and the suggestion is made that the Park Management should set a cap on the number of visitors within the park at any given time. The “healing” time is also important to the hundreds of species that call the park home, including at least 56 endangered species. A cap on numbers of visitors may sound draconian, but the park’s mission is to protect the natural ecosystems, rather than becoming just another amusement center.

At the same time, natural forces are still at work. Waves, storms, and the sea-level rise continue to erode much of the park’s shoreline, causing shoreline retreat, potential beach narrowing, and flooding (Rangel et al., 2015). The rates of these processes are highly variable, depending on rock types, their degree of fracturing and faulting, and the orientation of the respective shores relative to tectonic features such as faults. What will park management’s response be when one of the main beaches narrows, a campground floods, or a road is threatened by erosion. Hopefully, it will be to let Nature take its course, and for this Natural Park to remain Natural.

References:

- Colombia Travel Blog, January 2, 2017, Tayrona National Park to close for a month.

- Tayrona National Natural Park web site

- Rangel-Buitrago, N., Anfuso, G., Correa, I., Ergin, A., Williams, A.T., 2013. Assessing and managing scenery of the Caribbean Coast of Colombia. Tour. Manage. 35, 41-58.

- Rangel-Buitrago, N., Anfuso, G., Williams, A.T. 2015. Coastal erosion along the Caribbean coast of Colombia: magnitudes, causes and management. Ocean Coast. Manage. 114, 129-144.

- Williams, A.T., Rangel-Buitrago, N., Anfuso, G., Cervantes, O., Botero, C., 2016a. Litter impacts on scenery and tourism on the Colombian north Caribbean coast. Tourism Manage. 55, 209-224.