NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

By Adam Voiland and Alan Buis, NASA / Earth Observatory;

Colonies of coral polyps are some of the most prolific builders in the world. Coral polyps secrete a material that forms a hard calcium carbonate exoskeleton around their base. That hard base protects against marine predators, and generation after generation of polyps build new exoskeletons on top of the old. Over time, the process builds up coral reefs that can become quite large—in many cases, large enough to be viewed from space.

Coral reefs, sometimes called the rainforests of the sea, are one of the most prized ecosystems in the ocean. They are home to about a quarter of all ocean fish species, making them hot spots of biodiversity. They protect shorelines from storms, provide food for millions of people, and provide economic benefits by encouraging tourism. Despite their value, few of the world’s reefs have been studied. Some have been examined through expensive, labor-intensive diving expeditions, but many have never been surveyed at all.

“Right now, the state of the art for collecting coral reef data is scuba diving with a tape measure,” said Eric Hochberg, scientist at the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences. “It’s analogous to looking at a few trees and then trying to say what the forest is doing.”

As global temperatures rise and the ocean becomes increasingly acidic, many researchers are concerned that the future for the world’s reefs is grim. Observations to date suggest that 33 to 50 percent of Earth’s coral reefs have been significantly degraded or lost in recent decades. Some reef scientists think that most functioning reef ecosystems will disappear by the middle of the 21st century.

Hochberg shares the concern, but he also sees indications that some types of corals may be resilient. He argues that to make definitive statements about how reefs are changing on a regional or global scale, scientists need data that offers a big-picture view, not just snapshots of what is happening at certain sites.

To get this big picture view, Hochberg is leading a project that will use aircraft to monitor entire reef systems in Florida, Hawaii, Palau, the Mariana Islands, and Australia. The COral Reef Airborne Laboratory (CORAL) will use an airborne instrument called the Portable Remote Imaging Spectrometer (PRISM) to gather the data. PRISM will offer high temporal resolution and below cloud flight altitudes that make it possible to resolve spatial features as small as 30 centimeters (12 inches).

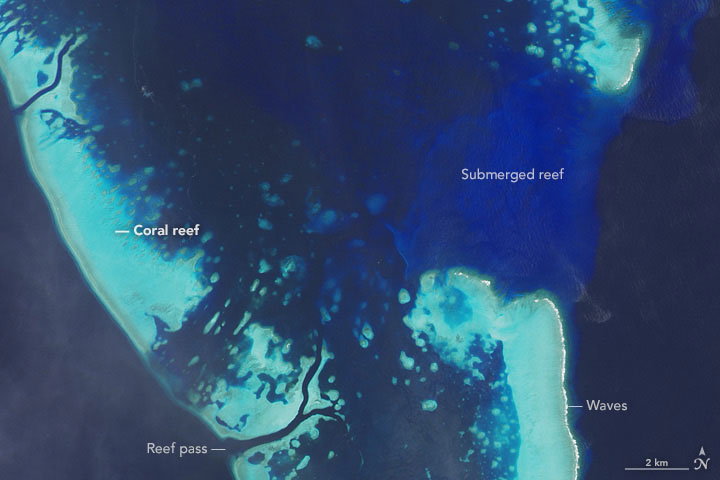

Hochberg’s team plans to visit the Republic of Palau, a chain of islands at the far western end of Micronesia. The island chain is comprised of 458 square kilometers (177 square miles) of dry land, and approximately 525 square kilometers (203 square miles) of reefs spread through the ocean. On March 21, 2014, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired a natural-color image of Palau. The top image highlights portions of Ngerbard and Kossel reefs, which are located to the north of Palau’s largest island, Babeldaob.

The reefs are turquoise, with actively growing colonies of coral appearing as a brown linear feature on the outer edges of the reef. Waves—appearing as a white line—are visible breaking along the eastern edge of some of the reefs. The different shades of blue are indicators of the depth of the water. The darkest blues are probably a few kilometers deep. The turquoise areas are covered with approximately one meter (3 feet) of water. The royal blue area is a reef submerged by about 20 meters of water. The channels in the reefs are called passes; they function as places where water can drain easily in and out of the lagoon as tides and winds change.

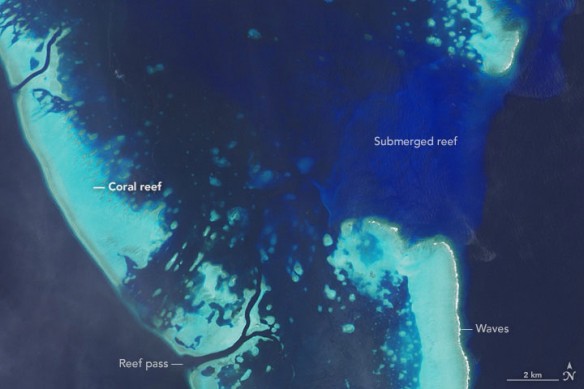

The second image offers a wider view of the reefs surrounding Babeldaob. About half of Palau’s reefs are barrier reefs. These appear in long stretches along island coastlines, separated from the shoreline by a lagoon. The western side of Babeldaob has a well-developed barrier reef system that extends about 150 kilometers (90 miles); the eastern side has some barrier reefs near the southern part of the island, but they are less developed and have gaps.

Palau’s second most common type of reef—fringing—accounts for about 37 percent of the country’s total reef area. Unlike barriers, fringing reefs develop adjacent to islands with little or no separation from the shore.

Reefs can evolve from one type to another over time. Fringing reefs are the youngest, forming around a volcanic island within a span of 10,000 years. Over the next 100,000 years, such reefs will continue to grow if conditions are right, becoming barrier reefs as the island erodes and subsides.

Although the CORAL campaign will increase the amount of data available on the health of coral reefs significantly, it will cover just three to four percent of the world’s reefs. “Ideally, in a decade or so we’ll have a satellite that can frequently and accurately observe all of the world’s reefs,” said Hochberg.

Original Article, NASA / earth Observatory