By Norma Longo, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

A headline from The Scotsman in August 2013 proclaimed “Shetland beach among best places in world to swim” and the news article following said “Despite its icy temperatures, a Shetland beach has been named among the best places in the world to swim, alongside those in the Caribbean, Australia and the Mediterranean.” This beach is St. Ninian’s Tombolo, a coastal feature that connects the southwest Shetland Mainland with St. Ninian’s Isle. The Isle’s name is a dedication to Shetland’s [unofficial] patron saint, Saint Ninian of Galloway, and the tombolo is known locally as an ayre, from the Old Norse Eyrr for ‘gravel bank.’ The village of Bigton on the Mainland is adjacent and offers good views of the tombolo.

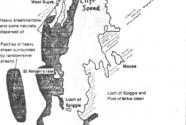

Lying off the southwestern coast of the Shetland Mainland, the 500-meter-long tombolo is the largest geomorphologically active sand tombolo in Britain. The ayre most likely formed during a period of rising relative sea level, during the Holocene epoch (Hansom, 2003). Flinn (1997) noted that for 300 years, the shape and position of the tombolo had not changed much, despite the mining of large amounts of sand for local industry, or from being submerged by waves during storms. Hansom wrote that the active body of sand migrated to the north about 30 to 40 meters in the early 20th century and then migrated slowly back to the south. Currently, it shows seasonal changes, with loss of sand from the center and gain at the ends in winter, and with sand returning to the center in the summer.

The Atlantic Ocean location features plunging cliffs on both the Mainland and the Isle, with no adjacent beaches to supply sand to the tombolo, as is normally the case with tombolo formation. The beaches of the tombolo face to the north and to the south and are flanked by dunes and blown sand on either end. The dunes and sand deposits form the sink for most of the nearshore sediment circulation system here. The blown sand volume at the eastern [Mainland] end is normally larger than that on the western end, which was the area used in the 1970s as a site for commercial sand extraction. The mining pit has since been filled in by blown sand, and low dune mounds are present. Some erosion is present both to the east and the west. (Hansom, 2003)

” Lying off the southwestern coast of the Shetland Mainland, the 500-meter-long tombolo is the largest geomorphologically active sand tombolo in Britain.”

— Norma Longo

The Blue Flag beach, a natural sand causeway between the two land masses, is made up of medium-grained sand with about 50% carbonate content over a base of shingle or rock at two meters depth. It consists of two concave arcs due to being subjected to waves from two opposing directions: arcuate waves approach from St. Ninian’s Bay to the south and from Bigton Wick on the north side. The fetch is limited to no more than two kilometers, which restricts some wave activity. The curve of the approaching wave crests exactly matches the arc of the beaches on either side of the ayre (Hall & Fraser, 2004). Ocean swell approaches St. Ninian’s Isle from the west-southwest, and the waves are diffracted and refracted around the Isle to meet and break on the tombolo, bringing sand from the sea floor via the wave action (Flinn, 1997).

The beach height fluctuates, and at times, during spring high tides or storm events, the middle of the tombolo, which is typically about 20 – 30 meters wide at high tide, is completely submerged. In addition, storms occasionally breach the ayre and the water typically flows through the resulting channel from north to south. Hansom points out that in the 1993 Braer storm, the center of the tombolo was underwater for several days. The storm was named for the oil tanker by that name that ran aground on the 5th of January 1993 on the west side of Garth’s Ness, to the south of St. Ninian’s Isle. The Braer was carrying nearly 85,000 tons of light crude oil and about 1,600 tons of fuel oil, all of which leaked out as the ship broke up and sank over a period of 12 days. This was more than twice the amount of oil that the Exxon Valdez spilled in Alaska and is noted to be the 14th largest oil spill in the world (ITOPF, 2013; Harris, 1995). It caused the largest ever pollution incident in Scotland. Oiled debris and seaweed were washed ashore and had to be removed. Of the 39 beaches considered at risk, 20 were oiled, and cleanup operations, incorporating both mechanical and manual methods, were required at 9 sites. Surface oil pollution reached northward beyond St. Ninian’s tombolo, which was one of the polluted sites cleaned manually afterward. None of the oil from the wreck was salvaged, but due to the heavy storms and the lightness of the type of oil, the spill was dispersed rapidly. Even so, land contamination and air pollution affected public health, agriculture, seabirds and animals, fisheries, and fish farming industries. The long-term effects were not as severe as they were initially feared to be, although some fishing had to be abandoned for several years because of the traces of oil found in the fish and shellfish. Millions of farmed salmon had to be destroyed because of contamination, as the fish could not escape from their cages to go to clean water. (Harris, 1995; M/V Braer oil spill links)

Animals on St. Ninian’s Isle itself may not have been affected. A local farmer uses the grassy island for grazing his sheep that cross the tombolo for access to the Isle. An interpretive sign at the eastern end of the tombolo notes that St. Ninian’s Isle was inhabited until 1775, and since then it has been used as a sheep farm. The high cliffs and sand areas of the Isle provide homes for rabbits as well as a variety of birds. The Isle (and most probably, the tombolo) also has a long history of human activity. In this historically important area, the remains of a 12th century chapel were found on the eastern side of the island. An archeological dig at that site uncovered a treasure of 8th century silver items hidden beneath the chapel floor. Archeological digs have also found remains of a pre-Norse chapel which overlay an Iron Age site. Burial grounds were found at each level.

The tombolo and Isle comprise a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), designating a protected area in the U.K. The Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) booklet (2011) provides this information: “SSSIs represent the best of Scotland’s natural heritage. They are ‘special’ for their plants, animals or habitats, their rocks or landforms, or a combination of these.” Further, “if you act without consent or intentionally or recklessly damage an SSSI’s natural feature(s), you may be committing a criminal offence, and if found guilty, fined. If you are convicted of damaging the natural feature(s) of an SSSI, by carrying out an activity without consent, a court may also make you repair the damage at your own expense.”

The tombolo beach was the winner in 2010 of the Keep Scotland Beautiful Seaside Award (STV, 2010), but in 2011 and 2012, a controversy developed when quad-bikes roaring up and down the beach and dunes created unwanted noise and caused disturbances to visitors and the ecosystem itself (Meyer, 2011). Some discussion was found in The Shetland Times. The tombolo was noted to have “large numbers of people on quad machines charging up and down the beautiful beach without a care for other visitors. . . leaving the acrid smell of distasteful burnt fuel that lodges in the throat. . . ” (Merrifield, 2011). Another writer said the machines sounded like giant mosquitoes and the noise went on all afternoon (Lawrence, 2011).

” St. Ninian’s Tombolo is a spectacular example of an active tombolo and is a beautiful beach for strolling, viewing wonderful scenery, and even swimming.”

— Norma Longo

The gist of the debate was that concerned people wanted the annoying and damaging machines banned from the beach. Opposing that view, one writer wrote: “What “fragility” exists at the site in question? The beach has been there for centuries without any protection from the very worst of anything and everything the Shetland climate and the western ocean could throw at it, anything that had any inherent “fragility” is already a very long time gone. I fail to imagine what a few motorbikes on an occasional weekend can possibly do to “destroy” something that has withstood lashing wind and rain, and driving sea for so long” (Garriock, 2011). The writer also mentioned that the bikers had been using the beach for decades. The controversy may not have been settled at the time of writing. The noise from the vehicles will likely continue to disrupt the typical quiet of the Shetland coast.The farmer drives his tractor across the tombolo to tend to his sheep on the Isle, but that wouldn’t create noisy disturbances equal to those from the quad bikes.

Meyer wrote [regarding SSSIs] in The Shetland Times that “Access rights conferred by the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 do not extend to the use of motorised vehicles for recreational use – unless the landowner has granted strict individual permission.” The following statement from the SNH website (2011) seems to deem the loud activity acceptable: “[The tombolo] attracts recreational vehicles, especially scrambling bikes and quads. This does not damage the tombolo where the tracking is restricted to soft sand below the high water mark, as wind and tides soon restore the natural shape. Use of vehicles within the dunes however leads to erosion and is damaging to the structure of the site.” Studies have shown that driving on beaches does damage the ecosystem and change the shape of the beach and dunes. Animals, including the microscopic fauna that live in the sand, and plants are detrimentally affected (Cooper & McKenna, 2009; Schlacher & Thompson, 2007).

St. Ninian’s Tombolo is a spectacular example of an active tombolo and is a beautiful beach for strolling, viewing wonderful scenery, and even swimming. Dogs and children enjoy the area and can play safely (on days the quad bikers are not present). Sea level rise and land subsidence doubtless will play roles in the future of the ayre.

References Cited:

- Cooper, J.A.G. and J. McKenna, 2009. Managing cars on beaches: A case study from Ireland. In: Williams, A. & A. Micallef, Beach Management. Principles and Practice. London: Earthscan Publishers.

- Flinn, D., 1997. The Role of Wave Diffraction in the Formation of St. Ninian’s Ayre (Tombolo) in Shetland, Scotland. Journal of Coastal Research, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 202-208.

- Garriock, M., 18 June 2011. Comment to Travesty at St. Ninian’s (Paul Meyer), The Shetland Times, Lerwick.

- Hall, Adrian and Allen Fraser, August 2004, updated 2013. Shetland Landscapes [Edinburgh, Scotland].

- Hansom, J.D., 2003. St. Ninian’s Tombolo (Coastal Geomorphology of Scotland). In May, V.J. and J.D. Hansom, Coastal Geomorphology of Great Britain, Geological Conservation Review, volume 28, chapter 8: Sand Spits and Tombolos. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, UK.

- Harris, Chris, 1995. The Braer Incident: Shetland Islands, January 1993. In: Section VI, The Braer Incident, International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings,I Volume 1995, No. 1: pp. 813-819.

- ITOPF: The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation Limited, 2013. ITOPF Oil Tanker Spill Statistics 2013, and View

- Lawrence, M., 7 June 2011. Spoiling the Attraction: Letter to the Editor, The Shetland Times, Lerwick.

- Merrifield, J., 7 June 2011. Letter to the Editor, The Shetland Times,

- Meyer, Paul, 13 June 2011 and 21 June 2011. Travesty at St. Ninian’s, Letter to the Editor (and comments), The Shetland Times,The Shetland Times, Lerwick.

- MV Braer oil spill, retrieved 2/27/14 at View and, View

and, View, and View - Pilkey, O.H., T.M. Rice, W.M Neal, 2004. How to Read a North Carolina Beach: Bubble Holes, Barking Sands, and Rippled Runnels. University of North Carolina Press, 162 pp.

- Schlacher, T.A. and L.M.C. Thompson, 2007. Exposure of fauna to off-road vehicle (ORC) traffic on sandy beaches. Coastal Management 35: 567-583.

- Scottish Natural Heritage, 2011. Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Battleby, Redgorton, Perth, 36 pp. (What owners and occupiers must do, p. 23) and View, and View

- STV, 15 Sept. 2010. Shetland beach rates best in Scotland. Glasgow: Scottish Television.

Additional Reading:

- Registers of Scotland, SSSI Register, 2007. St. Ninian’s Tombolo.

- Ritchie, W., M. O’Sullivan, Ecological Steering Group on the Oil Spill in Shetland, 1994. The Environmental Impact of the Wreck of the Braer. Edinburgh: Scottish Office Environment Department, 207 p.

- Smith, J., 1993. The Houb, Dales Voe: Coastal Processes. In Shetland Isles (J. Birnie, J. Gordon, K. Bennett and A. Hall, eds.), Quaternary Research Association Field Guide, Quaternary Research Association, p. 60.

- Wells, P.G., J.N. Butler, J.S. Hughes, 1995. Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: Fate and Effects in Alaskan Waters. Philadelphia: ASTM, 955 p.