By George Crozier and John Dindo

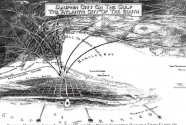

Dauphin Island is a “drumstick” shaped barrier island (16miles/26 km) on the western side of the main pass at Mobile Bay about 48 km (30 miles) south of Mobile, Alabama. The island is bounded to the northeast by Mobile Bay, to the north by Mississippi Sound and the Gulf of Mexico to the south. The eastern end is about 6.4 km (4 miles) long by 2.4 km (1.5 miles) wide sheltered by one of the largest ebb tidal deltas in the world. This remnant of the Pleistocene era rises from 1.5 – 3 meters (5-10 ft) to historic dune heights of what had been nearly 14 m (45 ft) above mean sea level.

“The relationship between the east end of the island and the ebb tidal delta, referred to as the “Sand Island/Pelican Island” complex, is extraordinarily dynamic and complex.”

— George Crozier & John Dindo

The Alabama National Guard routinely spent part of the summer pushing these massive dunes off of the three-room elementary school on the island. These massive dunes have gradually winnowed away so that there is only a remnant overlooking Pelican Bay.

The relationship between the east end of the island and the ebb tidal delta, referred to as the “Sand Island/Pelican Island” complex, is extraordinarily dynamic and complex. The ebb tidal delta may exist as one or two islands with the eastern-most referred to as Sand island and the western-most as Pelican Island – and at times there may be several ephemeral islands making up this unusual offshore barrier.

The 18 km (11 mile) Holocene barrier spit to the west has an elevation of no more than 2 m (6-7 feet) and is only 200 m – 350m wide throughout much of its length. This is the area routinely impacted by storm surge and the criticisms by various media rarely recognize the drastically different ends. The opposite ends of the island are indeed very different because the east end is of substantially higher elevation and heavily wooded maritime forest backed by coastal salt marsh. The problems that are attributed to Dauphin Island are most evident on the heavily developed “the west end” of the island – a strip only about 3-4 miles long where most of the insured loss and infrastructure destruction occurs.

The relative security of the east end of the island made it an attractive place for development in the early years of the last century. There wa s even a proposed “world port and coaling station” described for the northeast side of the island in 1920. It was further noted in this chamber of commerce flyer that the island had never been damaged by storm even though Mobile was hit by two major hurricanes in 1916.

The first bridge was built in 1955 and with vehicular access provided, development was inevitable. The ownership of the island was vested in a Property Owners Association (POA) and the island was subdivided in a typical mid-20th century grid providing about 3,000 individual lots. The POA developed covenants that essentially zoned the island and it kept the beach of the “west end” as a common holding of the association.

The normal pattern of storm impact has been the predictable overtopping of the low barrier with formation of dramatic overwash fans into Mississippi Sound. This event is promptly followed by appeals from the Town of Dauphin Island for relief from county, State and federal authorities. This usually involves a variety of processes moving sand from the overwash fans and returning it to the property owned by the POA or individual owners or as protective piles of sand. Fig. 3 by USGS demonstrates erosion by red and green is accretion. The red dots are (or were) houses.

Simultaneously the private owners filed for coverage under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The waterfront properties, some on Mississippi Sound to the north and most on the Gulf of Mexico to the south constitute less than 0.02% of Alabama’s land area but it has received 20% of the National Flood Insurance Program funding provided to the State over the years.

“Hurricane Katrina cut an inlet in the historically common location just west of the developed portion of the west end and effectively cut the island in half.”

— George Crozier & John Dindo

These protective barriers have never survived subsequent high energy exposure, leading to the ridiculous image below of “a day at the beach”.

The town’s budget depends to a large extent on the lodging revenues derived from the overwhelming number of west end properties. The request for aid in rebuilding these largely absentee landlord properties is understandable but there is very little public access provided so the result appears to be a massive subsidizing of private property within an essentially gated community.

Hurricane Katrina cut an inlet in the historically common location just west of the developed portion of the west end and effectively cut the island in half. No State or federal aid was available for restoring this area but a new “benefactor” emerged in the form of BP in the wake of the disastrous oil spill. Island interests argued that an “island made whole” was necessary for protecting the mainland communities and a rock wall was constructed under a one-year construction permit from the Corps of Engineers The oil spill impacts had virtually disappeared before the wall was completed. The project has been viewed locally as both maintenance of the storm barrier function as well as necessary for keeping appropriate salinities over oyster reefs in Mississippi Sound.

The town seized on the opportunity to acquire the ¾ of a mile west of the houses and began developing a beach that addressed the lack of public access AND generated some revenue by charging for parking and access to the new “public” beach.

Downdrift erosion of this area has been documented over and over again. In fact the most waterfront private lot immediately adjacent to the park is in fact now a “water -under” lot. Meanwhile the existing waterfront owners have recognized the erosional rate and have constructed seawalls which have been euphemistically recognized by the State as “sand retention systems”. Seawalls on the Gulf beaches are prohibited by regulations under the State’s Coastal Area Plan – apparently sand retention systems are not! Fig. 8-11.These pictures were taken late spring and the summer of 2013 by John Dindo.

The town and state authorities are so intimidated by the threat of a “takings” ruling that they have allowed this pattern of development to seriously jeopardize the $3 million investment in the public beach. Having opened the “floodgates”, other property owners have installed sand retention systems to protect their property also, Figures 10-11. Figure 10 also shows the current sand pile designed to protect the town’s infrastructure, the most recent FEMA –paid construction. This is supposed to protect the roads,water and sewer, as well as the power poles.

“Seawalls on the Gulf beaches are prohibited by regulations under the State’s Coastal Area Plan – apparently sand retention systems are not!”

— George Crozier & John Dindo

The town of Dauphin Island and the Property Owners Association are trying to obtain $30-70 million from the State’s portion of the RESTORE Act (BP oil spill settlement) arguing that the island provides significant protection to the mainland and preserves appropriate salinities for the fisheries using Mississippi Sound. It is argued that New Jersey received $1Billion from Hurricane Sandy but according to Wikipedia “Over two million households in the state lost power in the storm, 346,000 homes were damaged or destroyed,[2] and 37 people were killed. Storm surge and flooding affected a large swath of the state” – not a good comparison!

There are ongoing negotiations with the Corps of Engineers to construct and maintain some kind of sand bypass system at the mouth of Mobile Bay which would nourish the entire island from east to west but other than that there are no commitments for any more relief when that sand disappears. Oh well, there will probably be another hurricane with all its subsequent relief!