By Gary Griggs, Distinguished Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Director Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz;

California is known for its beaches. Although the Golden State has a lot of coastline, 1100 miles to be more precise, but only a bit over 300 miles of that consists of sandy beaches that are easily accessible to the public. If we divide those 300 miles by the state’s 38 million people, each person only gets about half an inch. Looking at those beaches another way, if we make some reasonable calculations for California’s total beach area, we each get about 24 square feet, just enough for a large beach towel.

Fortunately, everyone in the state doesn’t go to the beach at the same time, except during the summer and on holidays and weekends. On the other hand, there are also millions of visitors to the state who come to visit the beaches, adding to the pressure on this iconic sandy resource.

“Monterey Bay holds the dubious distinction of being the only active beach sand mining operation along the entire United States shoreline. To make matters even worse, it all takes place along the shoreline of a protected National Marine Sanctuary.”

—Gary Griggs

With usage of beaches in the state being very high, there has been a lot of attention focused in California on littoral cells and beach sand budgets, and to what extent sand supplies have been altered or reduced by human activities. While it has always appeared that there was an infinite amount of beach sand around, as we have studied and monitored beaches more carefully in recent years, it turns out that there are limitations to beach sand.

While the largest number of people in California head for the beaches and warm waters of Southern California, the 30-mile long, continuous sandy shoreline around Monterey Bay is the most visited stretch of shoreline on the central coast. This is where the inhabitants of Silicon Valley and the greater San Jose region head to escape the summer valley heat. This white crescent presents a complete range of beach experiences. For those who prefer crowds, there is the densely populated Main Beach in Santa Cruz, adjacent to the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk (Figure 1). Here you can share your small piece of the beach with thousands of others with an amusement park in the background complete with the screams of those on the rollercoaster. At the other extreme are the more remote beaches along the central and southern shoreline of the bay, just 10 or so miles away, where you need to hike in but then may only see several other people all day (Figure 2). The entire bay shoreline is part of one of the nation’s largest National Marine Sanctuaries, while the northern end of the bay from Steamer Lane (Figure 3) to Pleasure Point has recently been named one of a handful of World Surfing Reserves.

While California has a number of well-recognized arcuate or hook-shaped bays (Half Moon Bay, Bodega Bay, the Silver Strand, and many more), Monterey Bay is unique in the state in being a double-ended hook shaped bay (Figure 4). Resistant headlands at both ends anchor the corners while wave refraction has created the long, smooth, gently curved shoreline that unwinds from both ends towards the middle.

Wave refraction moves sand along the shoreline from both northern and southern beaches towards the middle of the bay where one of the largest submarine canyons in the world drains about 350,000 cubic yards of beautiful white sand offshore into very deep water, never to be seen again.

There are two other major sinks for the large volumes of sand that move along the shoreline of the bay, one natural and one very unnatural. During the low sea levels of the last Ice Age, which came to a close about 18,000 years ago, the offshore continental shelf was a depositional site for millions of cubic yards of sand carried by the region’s rivers and streams. Strong onshore winds blew the fine-grained sand landward and built an impressive area of coastal dunes that cover about 40 square miles and at one time extended nearly six miles inland. Most of these inland dunes are now vegetated and stabilized. As sea level rose in response to glacial retreat, the shoreline migrated inland and eroded back those dunes. Today, an eroded dune face marks the back edge of most of the central and southern bay shoreline (Figure 5). Because of this lack of connection between the modern beach and the dunes, not much sand actually leaves Monterey Bay’s beaches today through aeolian transport.

“…we have studied and monitored beaches more carefully in recent years, and it turns out that there are limitations to beach sand.”

—Gary Griggs

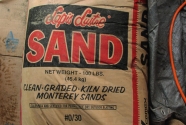

There is another huge sink, however, a human sink. For nearly a century the rounded, coarse-grained, amber colored sand of the southern bay’s beaches has

been mined for a number of industrial uses: filtration, sand coatings and blasting, grouting, and even for filling of utility trenches. At one time there were as many as 5 commercial sand mines operating along the shoreline, using drag lines and large scoops to pull sand right off the beach (Figure 6). From records kept by permitting agencies, best estimates are that 200,000 to 250,000 yds3 were extracted annually for decades.

While the smooth crescent shape of the southern bay suggested long-term equilibrium, with the removal of hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of sand year after year, erosion of the dunes had become obvious several decades ago. Stilwell Hall at the former Fort Ord military base (Figure 7), the Monterey Beach Hotel and the Ocean Harbor House condominiums (Figure 8) all became progressively threatened by bluff retreat at average rates ranging from 2 to 8 feet per year. Unconsolidated dune sand really doesn’t provide much resistance to wave attack once the protective beach is narrowed. Armor has been the solution at all three sites, with Stillwell Hall, the former World War II soldier’s dancehall, finally being demolished and its riprap removed, while concrete seawalls have constructed on the beach at the other two sites. In both of these latter cases, beach narrowing during winter months of storm wave activity leads to loss of lateral public access at high tide as the shoreline is squeezed up against the concrete seawalls (Figure 9).

Following the documentation of erosion rates and the connection to sand mining volumes, as well as severe erosion in first three months of 1983 during the most damaging ENSO event in half a century, all of the mining permits but one were terminated in the late 1980s by the State Lands Commission. The only distinction between the sand mining operation that continues today and those that were closed down was that the sand removal takes places from a pond on the back beach (Figure 10), rather than from a dragline across the shoreline itself, and that the mining company (CEMEX) is based in Mexico. Following the closure of the other mining operations, CEMEX increased their removal rate to the equivalent of all of the previous mining operations combined. The reduction in the number of beach sand mines did not affect the total amount of sand being removed (Figure 11).

Despite California’s love of its beaches, the clear connection between the bluff erosion rates and the sand removal volumes, and a statewide agency that has been in existence for nearly 40 years to protect coastal resources and control shoreline development, beach sand removal continues at about 200,000 yds3 per year.

“…beach sand removal continues at about 200,000 yds3 per year, and to date, absolutely nothing has been done to halt this travesty to the shoreline and beaches of Monterey Bay.”

—Gary Griggs

To my knowledge, it holds the dubious distinction of being the only active beach sand mining operation along the entire United States shoreline. To make matters even worse, it all takes place along the shoreline of a protected National Marine Sanctuary. Something is seriously wrong with this picture.

During the last two centuries, the beaches of Monterey Bay were seen as resources to be utilized when populations were much smaller, beach use was much less intense and environmental concerns were nearly non-existent.

The beaches of the northern bay are characterized by seasonal concentrations of black sand. In addition to iron bearing minerals such as magnetite, chromite and ilmenite, black sand may contain small amounts of gold, platinum and other rare heavy metals. A black sand gold rush started in the summer of 1860, and by August, miles of beach had been staked off and more than 25 mining claims filed (Figure 12). The digging continued up until the 1880s when one family drilled a tunnel 300 feet long into the bluff and for a time were extracting $5 of gold for each ton of sand.

For a short while in the 1920s, the Triumph Steel Company laid claim to nearly 2 miles of beach along the northern Monterey Bay shoreline and was mining the black sand, which contained 500 to over 1000 pounds of magnetite per ton of sand. They used a magnetic separator to remove the magnetite and then used a furnace to produce a red iron oxide that was used to make paint. While this happened in the 1920s without any real outcry, opposition, or environmental concerns, mining beach sand and setting up a furnace on the beach would not be viewed favorably today.

But times have changed. Thousands of beach visitors, a California Environmental Quality Act, the creation of the California Coastal Commission as a statewide regulatory body in the mid-1970s, and in 1992, the establishment of the nation’s largest National Marine Sanctuary. Yet CEMEX continues to extract beach sand in large volumes, and to date, absolutely nothing has been done to halt this travesty to the shoreline and beaches of Monterey Bay.