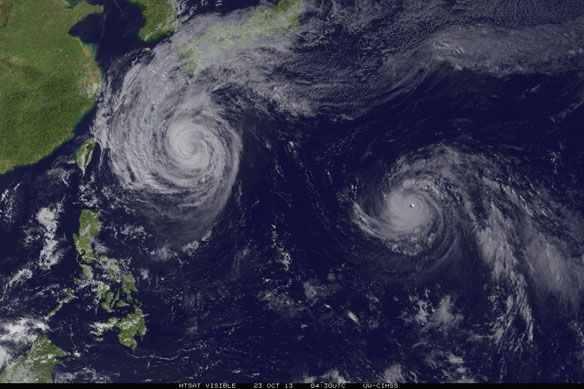

Typhoon Francisco and Super Typhoon Lekima on October 23, 2013 as they tracked northwestward toward China and Japan. (Credit: Tim Olander and Rick Kohrs, SSEC/CIMSS/UW-Madison, based on Japan Meteorological Agency data.)

By NOAA;

Researchers find that the average latitude where tropical cyclones achieve maximum intensity has been shifting poleward since 1980

Over the past 30 years, the location where tropical cyclones reach maximum intensity has been shifting toward the poles in both the northern and southern hemispheres at a rate of about 35 miles, or one-half a degree of latitude, per decade according to a new study, The Poleward Migration of the Location of Tropical Cyclone Maximum Intensity, published tomorrow in Nature.

As tropical cyclones move into higher latitudes, some regions closer to the equator may experience reduced risk, while coastal populations and infrastructure poleward of the tropics may experience increased risk. With their devastating winds and flooding, tropical cyclones can especially endanger coastal cities not adequately prepared for them. Additionally, regions in the tropics that depend on cyclones’ rainfall to help replenish water resources may be at risk for lower water availability as the storms migrate away from them.

The amount of poleward migration varies by region. The greatest migration is found in the northern and southern Pacific and South Indian Oceans, but there is no evidence that the peak intensity of Atlantic hurricanes has migrated poleward in the past 30 years.

By using the locations where tropical cyclones reach their maximum intensity, the scientists have high confidence in their results.

“Historical intensity estimates can be very inconsistent over time, but the location where a tropical cyclone reaches its maximum intensity is a more reliable value and less likely to be influenced by data discrepancies or uncertainties,” said Jim Kossin, the paper’s lead author, who is a scientist with NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center currently stationed at the NOAA Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Consistent with this poleward shift, many other studies are showing an expansion of the tropics over the same period since 1980.

“The rate at which tropical cyclones are moving toward the poles is consistent with the observed rates of tropical expansion,” explains Kossin. “The expansion of the tropics appears to be influencing the environmental factors that control tropical cyclone formation and intensification, which is apparently driving their migration toward the poles.”

The expansion of the tropics has been observed independently from the poleward migration of tropical cyclones, but both phenomena show similar variability and trends, strengthening the idea that the two phenomena are linked. Scientists have attributed the expansion of the tropics in part to human-caused increases of greenhouse gases, stratospheric ozone depletion, and increases in atmospheric pollution.

However, determining whether the poleward shift of tropical cyclone maximum intensity can be linked to human activity will require more and longer-term investigations.

“Now that we see this clear trend, it is crucial that we understand what has caused it – so we can understand what is likely to occur in the years and decades to come,” says Gabriel Vecchi, scientist at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and coauthor of the study.