By Michael Carlowicz / NASA

Scientists have known for years that the shape of the seafloor plays a role in how tsunami waves build up as they approach the coastline. Underwater topography also determines why some areas get hit worse than others.

But in the wake of the Tohoku-oki tsunami, scientists now know that seafloor topography affects the strength and height of a tsunami even in the deep ocean and at great distances from the genesis of the wave.

Scientists had suspected that underwater mountains and chasms, as well as islands, played a role in deflecting tsunami waves in some places and amplifying them up in others. But it was not until three satellites passed over such waves in March 2011 that they could confirm it.

Researchers from NASA’ Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the Ohio State University (OSU) used satellite altimeters to observe “merging tsunamis”—wave fronts that combine to form single waves at double the previous height. Such waves can travel hundreds to thousands of kilometers without losing power.

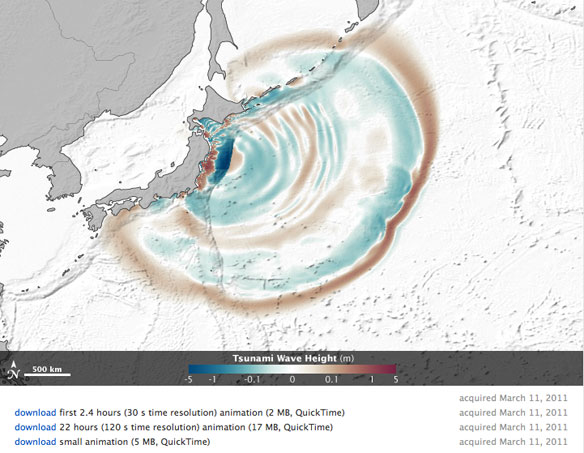

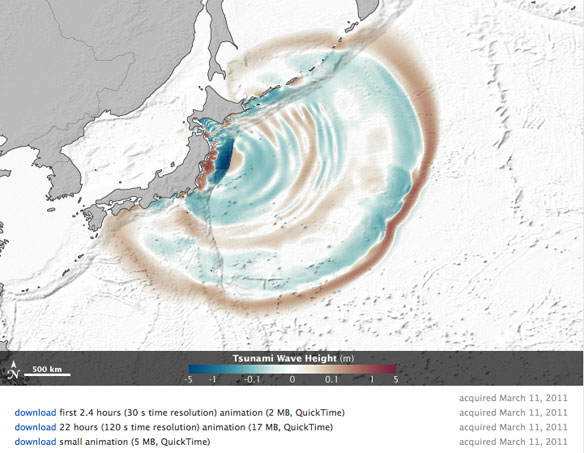

The image above comes from a data-based computer model that shows how the waves can refract, bend, and merge as they propagate. Waves peaks are depicted in red-brown, while depressions in sea surface appear in blue-green. Grayscale outlines show the location of mid-ocean ridges, peaks, and islands. You can also view the animated model, which reveals the motion across the Pacific basin.

The team examined measurements of the wave fronts as gathered by the Jason-1, Jason-2, and Envisat satellites, each of which flew over the tsunami at a different location. Altimeters on each satellite measure sea level changes to an accuracy of a few centimeters. They found that the March 2011 tsunami doubled in intensity when passing over rugged ocean ridges and around islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. They verified their satellite observations by comparing with data from Global Positioning System (GPS) sensors and buoy data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) program.

“It was a one in ten million chance that we were able to observe this double wave with satellites,” said Tony Song, principal investigator of the study and a scientist at JPL.

“Researchers have suspected for decades that such ‘merging tsunamis’ might have been responsible for the 1960 Chilean tsunami that killed about 200 people in Japan and Hawaii, but nobody had definitively observed a merging tsunami until now.

It was like looking for a ghost. Jason happened to be in the right place at the right time to capture the double wave.”

Wreckage and Recovery in Ishinomaki: Japan

By Michon Scott / NASA

February 21, 2012.

March 14, 2011.

At the northern end of Sendai Bay, Ishinomaki once boasted one of the world’s largest fish markets. On March 11, 2011, the earthquake and tsunami destroyed about 28,000 of the port city’s houses. More than 3,000 residents perished, and nearly three months later, almost as many people remained missing.

These false-color images compare conditions in Ishinomaki immediately after the earthquake and tsunami, and then a year later. The top image, acquired by the Advanced Land Imager (ALI) on NASA’s Earth Observing-1 (EO-1) satellite, shows Ishinomaki on February 21, 2012. The bottom image, acquired by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA’s Terra satellite, shows the same area on March 14, 2011.

In these false-color images, water is blue, vegetation is red, and bare ground and urban areas range from blue-gray to pink-beige. Ishinomaki is a mixture of agricultural fields, homes, and businesses. Along the coast lies the Matsushima Air Field, identifiable by its runways. The Old Kitakami River snakes through the region, draining into Sendai Bay east of the city center.

The biggest difference between these images is the retreat of flood water. In March 2011, standing water swamps fields on both sides of the river, and north of the airfield. Eleven months later, the water has retreated.

Although Ishinomaki dried out in the year following the tsunami, it hardly returned to normal. The coastal plain along Sendai Bay experienced some of the farthest-reaching tsunami waters. Both low-lying and heavily urbanized, Ishinomaki was one of the hardest hit by the March 2011 event.

Having experienced several tsunamis in recorded history, Japan is better-prepared for such events than perhaps any other country. Sea walls and breakwaters line almost half of Japan’s coastline, and they could counter the roughly 4-meter (13-foot) walls of water from the kind of tsunami that strikes every 150 years or so. But the March 2011 earthquake sent a 20-meter (65-foot) wall of water to the city.Coastal forests that were planted to provide protection from the sea were instead transformed by the potent waves into thousands of battering rams.

A year after the earthquake and tsunami, rebuilding Japan’s coastal cities to withstand tsunamis remains a challenge.