By Blair and Dawn Witherington

Jekyll Island is a 12-kilometer long ark meeting the Atlantic Ocean as part of the Georgia coastline, southeastern US. The island is an exquisite exemplar of coastal processes, both geological and human-influenced.

The north end of Jekyll is sinking. Although sufficient open sand remains at low tide, each high tide brings the Atlantic into the maritime forest of live oak and slash pine. The result is a boneyard beach scattered with a skeletal testament to coastal change.

A little farther south on Jekyll, the ocean washes up at the feet of human endeavor. There, tides advancing on beachfront buildings and parking lots have compelled human intervention in the form of granite revetments dumped onto the beach. It’s more difficult to walk on and comparatively less picturesque that the adjacent, stately, ghost forest, but the rocky battleground does offer its own interesting philosophical instruction.

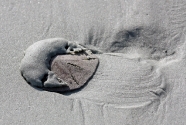

The dynamic drift of sand that has impoverished Jekyll’s northern beaches has fattened the island’s southern shoreline, where tall dunes front a maritime forest of salt-spray-tortured bonsai-shaped oaks. The line of dunes stretches south, ending at a broad sandy fan at the island’s southernmost tip. The expanse invites resting seabirds and provides living space for a splendid variety of imbedded marine animals. Some of these are visible at low tide, and others exclaim their presence only by their skeletal remains—the knobbed whelks, baby’s ears, shark eyes, and other shells prized by collectors of beach-trip souvenirs.

Jekyll Island is among the most easily accessible of Georgia and South Carolina’s “sea islands,” many of which are strikingly beautiful and similar to the landscape occupied by the Native American Guale people who persisted for hundreds of years as frequent coastal visitors. These folks were vanquished by European conquest and assimilation, rather than by natural forces. The winners of this cultural battle now occupy Jekyll Island and other laboratories of coastal change. Amidst some messy experimentation, there remains some beautiful scenery and wildlife.

Living Beaches Of Georgia And Carolinas, By Blair and Dawn Witherington