By Andrew Cooper, in The Geographical Journal

With oil continuing to spill into the Gulf of Mexico from BP’s Deepwater Horizon platform, Andrew Cooper reflects on natural and man-made crises, environmental threats and issues of coastal risk and resilience. The author, in collaboration with John McKenna, has previously published on coastal protection strategies in the autumn issue of The Geographical Journal.

The close relationship between human activities and the ‘resilience’ of coastal regions has been highlighted by successive natural events, such as tsunamis and hurricanes, and man-made crises like the recent oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coast of Australia.

We use the term ‘coastal resilience’ here to refer to the ability of a coast to cope with (i) impacts on the natural ecosystem (ii) impacts on the humans who derive benefit from coastal resources and (iii) interactions between humans and the environment. Geographers have a critical role to play in helping to make sense of this multifaceted concept of resilience, guiding coastal strategy and informing national and international policy and best practice.

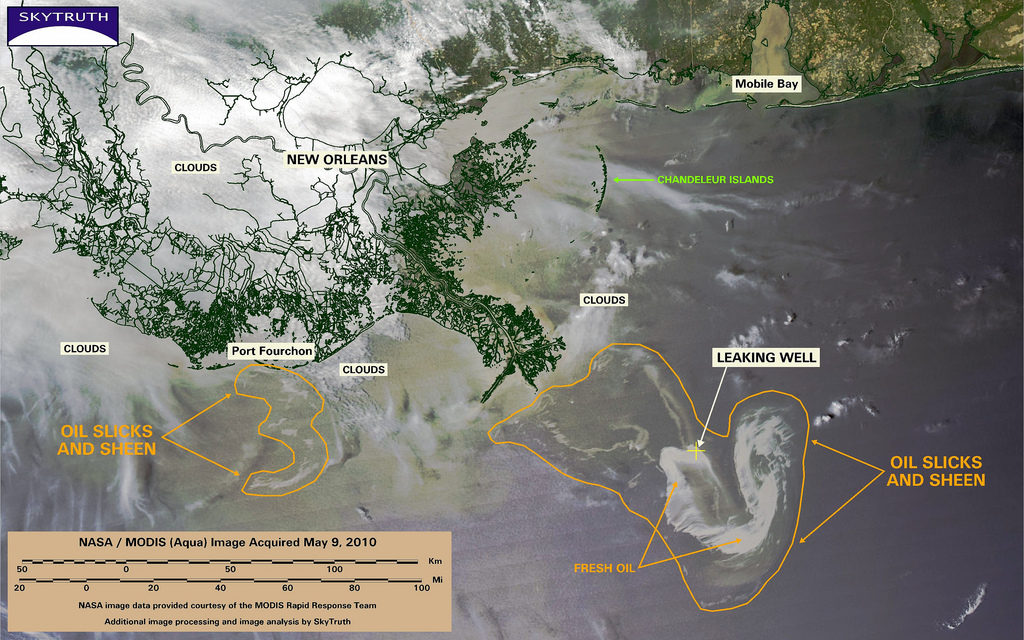

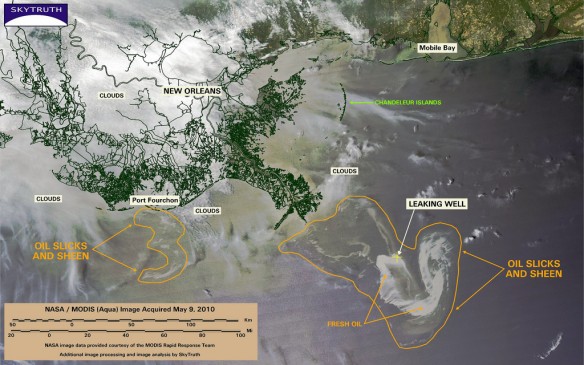

The size and anticipated impacts of the massive oil spill (May 2010) in the Gulf of Mexico quickly focused people’s minds on the fragility and vulnerability of the Gulf coast in the same way that the threat to the Great Barrier Reef was clear from the recent grounding of a ship in April 2010. Oil spills present an immediate, dramatic and visible threat to coastal systems. Their impact can, however, be short-lived if the spill is contained and many ecosystems can indeed recover fairly quickly as we have seen elsewhere. At Gladstone, Australia, for example a mangrove ecosystem affected by an oil spill in January 2006 was well on the way to recovery two years later (Melville et al., 2009). There can, however, be immediate and large scale impacts on human activities like fishing, tourism and recreation, which is exercising the minds of Gulf coast communities and coastal managers at the moment.

Human nature being what it is, our immediate focus seems to be on protecting the more visible parts of the ecosystem (like birds), and less on the other important constituents that are often microscopic (algae, plankton etc). Spraying detergents to disperse the oil and protect the birds might even have more serious and long-lasting impacts on the microscopic marine life on which all the visible parts of the ecosystem depend. Paradoxically, it might be better to let some oil wash up on the coastline making it easier to clean up. In the Gulf this would require sacrificing the immediate coastal margins of saltmarshes which would be politically very difficult because of the high visual impact and negative publicity that could ensue.

In contrast to the dramatic impacts of oil spills and hurricanes, there is a far more pervasive and long-lasting threat to coasts that arises from urban development. While it is not so dramatic or rapid as storms or oil spills, it is causing more and more of the coast to be defended, either with hard coastal defences or artificially nourished beaches and is fatally inhibiting the coast’s resilience. This activity is tying society into an unending commitment to maintain coastal defences in order to protect property – and when that commitment falls short, as in the case of Hurricane Katrina, the results can be devastating. Natural coasts, in contrast, cope with hurricanes and tsunamis as they have always done, by adjusting their shape during the event and then recovering to a new equilibrium within a short period of time. When there are buildings to protect, we don’t allow this to happen and so the natural resilience of the coast is impeded and it is permanently damaged.

Working with natural processes can help minimise the destructive power of the sea-in fact, the destructive power of the sea comes to be seen as simply an increase in the intensity of coastal processes as long as no human infrastructure is at risk. Although ‘working with natural processes’ means different things to different people, in our 2008 paper we contend that the true sense of the term implies allowing coasts room to adjust themselves. So-called soft engineering such as beach nourishment or dune restoration is often regarded as ‘working with natural processes’ but it is not a long-term solution. It might ‘patch up’ current problems but ties society into an unending commitment to continue the practice at considerable cost to this and future generations. A deliberate decision to not protect some existing coastal property needs to be taken alongside a decision to properly control future development at the coast if we are to achieve the ideal of working with natural processes to maintain coastal resilience.

At a time of global sea level rise, coasts are adapting their shape to adjust to these changed circumstances. This will mean coastal erosion in some (most) places and accretion in others as the coast re-equilibrates. For this adjustment to happen, the coast needs adequate space – a concept partially embodied in the UK in government’s ‘making space for water’ policy. Building on low-lying land or even artificially constructed land as in the Persian Gulf at a time of rising sea level emphasises the disconnect between what scientists know about coastline response to rising sea level, and human systems for developing, let alone regulating coastal development. When the Maldives government is talking seriously about finding a new homeland because of the threat of rising sea levels, artificial islands, very like the sand islands of the Maldives, are being constructed off Dubai. In spite of the threats faced by rising sea level storms, oil spills and so on, we are modifying and distorting our coastlines more than ever and in so doing are reducing their resilience.

Allowing coasts the space and time to function naturally maintains their resilience and creates the best natural protection for society against coastal hazards. Building either on mobile coasts and/or attempting to stabilise them, seriously impairs that resilience.

As events in the Gulf of Mexico suggest, our approach to marine and coastal management might yet prove inadequate, especially if we continue our current mad phase of coastal development and persist in delving further into the unknown by drilling for oil resources in ever deeper and remoter regions of the seabed. Oil spills dramatically focus our attention on the fragility of coastal ecosystems but our bigger challenge is to regulate development.